Agasthya

A newsletter on the Natural History, Ecology

and Conservation of the Agasthyamalai region, Western Ghats, India.

Requeim for Madhuca

The first time I saw Madhuca longifolia trees were in Kallidaikurichi. These trees were truly grand and imposing at over 70-80 feet and must have been about 70 years old. They stood within the compound of an ancient shaivaite temple on the outskirts of the town. I was accompanying a team of kids from Singampatti village and colleagues from KMTR field station, to do a bat count. The bats (Pteropus giganteus) had colonised these Madhuca trees and to me they appeared like ripened fruits, hanging from the trees. Over the last four years that ATREE researchers have been monitoring this colony, their numbers have remained steady at about 3,000.

However, in June a group headed by Dr Ganesh could spot only 500 odd bats. Curious to know why, the next day, some of us headed for the temple to investigate. Nearing the temple, we got a shock when blue open skies greeted us where some of the Madhuca trees stood. Almost all the trees on which the bats roosted, except for two, had disappeared. A feeling of remorse and anger swept over us. Someone suggested we check with the "kanaku pillai" (accountant and manager) of the temple to know why the trees had been felled.

'Accounts Pillai' nonchalantly informed us they had taken permission of the forest dept. to cut down the trees. The trees were required for making a temple chariot for one of their many temples. It did not matter that thousands of bats considered the trees their home for years. Temple chariots were more important. I thought of the hue and cry we make when we human beings lose our homes in similar situations. But, the bats are more gracious. They would hopefully forgive us our sins and move on to some other grand old Madhuca somewhere in the landscape waiting for yet another "kanaku pillai" to close its account.

Twinkling lights

When you take the late night bus to Nalmukh from Kallidaikurchi you wish for two things: a seat next to the driver or a window seat. Sitting next to the driver, with some luck, you may sight some wildlife, but with a window seat you need no such luck to see the beautiful twinkling lights from the crowded plains below. When we first saw these lights in the early 90’s the twinkles were islands of light but today many of these islands have merged and many more are merging and emerging rapidly.

The reasons are simple: The landscape outside the tiger reserve is transforming rapidly. Land in any form: wild, rocky, water logged, bushy or just flat and open, is giving way to residential plots; lake beds are being encroached and soil from tank beds are being carted away by tractor loads for the mushrooming brick kilns fuelled by palm trees. Would the twinkling lights continue to merge then?

On a recent visit to the forest office at Tirunelveli we glanced upon some documents prepared for tiger reserve management . There were two fat books: one, a management plan for the reserve and another - a little slimmer one - on managing the buffer outside the reserve boundary. It is good to know that plans are emerging to designate a buffer outside the tiger reserve.

The twinkling lights would continue to twinkle, but we hope it does not become one large haze of light.

I hope you had the opportunity to look at our web version. We now have plans to get a Tamil version of Agasthya and make more people from the landscape share their joys and concerns about the Agasthyamalai mountains.

Happy reading

T.Ganesh

Our 'lucky' telescope

On 9th June, 2009, early morning, we went into Manimuthar forest to make observations on owl roosts. Manimuthar with dense scrub forest and teak plantation harbours Sambar deer, leopard, Sloth bear, elephant, wild pig and some other small mammals too. We have often seen Sambar and pigs on the fringes of the forest, but never seen a leopard or sloth bear except for their signs.

Ganesh, Muthu and me were scanning for owl roosts in three different directions from a vantage point. Soon I saw an owl flying to its roost and I was zooming on it. Just then Ganesh called for my attention to check if I could see something on a rock which was quite far away. I told him that I see some thing like a tail of a leopard without taking away my eyes from binoculars.

We had a telescope with us, but without a stand. We immediately made an improvised stand using dry sticks. Muthu and me, looked through the telescope and were highly excited to see the mother and its cub enjoying the morning sun resting next to each other. Muthu was so excited that he did not want to take his eyes off the lens.

While we were stalking / ‘telescoping’ our attention on the leopards, we heard a growling sound from the forest. We panned our eyes in the direction of the sound. Again Ganesh pointed at a Sloth Bear mother with two cubs. The mother was urging her cubs to follow her up the hill but they were more curious to investigate the thorny bushes and boulders along the way. Two days later we again went into the forest and that time too, we heard strange noises. Muthu however felt it could be a langur hooting and sure enough it was. Though we complimented the new telescope as it brought luck on us for the sightings, our skills in wildlife tracking are also getting sharpened with time spent in the forest and good guidance.

'Ground truthing' KMTR

The period that I spent as an intern at the Singampatti field station and throughout the KMTR region was profoundly memorable. My previous research during my undergraduate and graduate studies at McGill University had focused entirely on eastern Canada, so my first foray into learning about the ecology of the Western Ghats in India was somewhat akin to a linguist encountering a new and exotic language for the first time.

Under the supervision of Dr. T. Ganesh, I am currently conducting a study of land use and land cover change in and around KMTR using a series of satellite data from the early 1970s to present. My field work during November and December 2008 involved the collection of GPS ‘ground truthing’ data that is necessary to classify our time-series of remote sensing data.

My time in the field was short, but I left the region feeling that I had gained a plethora of information and insight about certain ecological and socioeconomic issues relating to the south Western Ghats. The brevity of my trip was perhaps the most eye-opening part of this experience, since much of my university education back in Canada had included studying aspects of global biodiversity, land use change, and conservation issues, in addition to international development.

Most importantly, I feel I gained a slightly better understanding of some of the multiple and highly complex issues surrounding the role of protected areas in conservation of this and other regions. I am also particularly glad to know that there is a team of dedicated researchers working to better understand these issues in places like KMTR.

- Graham MacDonald

Chilling facts of chilli fields

Bright green paddy fields are set against the backdrop of KMTR hills over which clouds play hide-and-seek. Shimmering water flows from the canal into the fields. Egrets, ducks and Ibises form tracks across the sky. A strong breeze or occasional slight drizzle interrupt the peafowl's call and in the fading light, you hear the sound of cattle and goats returning home.

One such gorgeous evening, in Singampatti, I joined Ganesh, Sam and field assistant Anand on a visit to the paddy fields to check for the presence of rats. On one side of the field, a farmer was cultivating chillis. Walking around this field, we were met with a strange smell. The owner of the chilli field was around, busy checking the plants for damage caused by pests. As we got into a conversation with him, he worried about the damage caused by insects. He was dreaming of huge profits by selling chillies if he could keep the pests at bay.

To achieve this he had been trying out different pesticides every week. The only constant was monocrotophos which we could smell. He rattled out with great pride names of at least 12 different pesticides he had used. His weapons of mass destruction had decimated earthworms, frogs, crabs, rats and also snakes in his field. The climax of this murder story came when he spoke ecstatically about a mongoose which ran from his field after being gassed and died inside the hollow of a nearby tree!

It is not just one farmer, but all farmers cultivating chillis in this area use huge amounts of pesticides. They are impervious to the possible ill-effects these toxic chemicals are having on them, their customers or the water bodies around here. Like one other farmer who stopped cultivating chillies mentioned; “it's not chillies we are cultivating, but monocrotophos.”

- Abhisheka Krishnagopal Top

Collecting GPS points in paddy fields

Photo: Graham MacDonald

Close encounters of the wild kind

These past four years at Kodayar, deep in the heart of the tiger reserve have been most memorable. The excitement of seeing rare animals in a rainforest is hard to articulate. Having experienced so many amazing sights and sounds, it is difficult to decide where to start. Witnessing the elusive Niligiri martin; not one but two, following a troop of LTMs(Lion-tailed macacaques) high up in the rainforest canopy, to almost running into a large male Gaur standing in the middle of the road on a particularly dark and foggy morning are two such incidents. But there are some instances that remain etched in my memory.

A trip to Muthuikuli vayal is always full of expectation. Owing to its location and the habitat, the chances of seeing wildlife are very good. But nothing could have prepared me for the sight I witnessed in February this year. As we were approaching the last saddle of the reservoir, we saw a herd of Niligiri Tahr no more than 20 feet away. They ran across the track and made their way up a hill and were gone before we could get our cameras out. The surprise at seeing so many Tahr - 26 to be exact - in their element, running up a rock face was awe-inspiring.

A tiger sighting in KMTR is very rare and always looked upon with much skepticism and to get questions like “Are you sure they had stripes and not spots” are quite common. I was at the receiving end when I saw two tigers one morning in April. We had been seeing signs of tigers, like scat and pugmarks but to see the real thing in an evergreen forest will rate as the most unforgettable.

Chilli fields of Singampatti in the background

Photo: Abhisheka Krishnagopal

Ten sunny days

To the people of Kallidaikurichi, a Chinese face is a rarity. I don't think they'd seen one in flesh and blood until I stepped off the bus. They have, however, seen Jackie Chan in Tamil dubbed English movies. And so, for ten days, I was Jackie, and expected to teach little kids kung-fu.

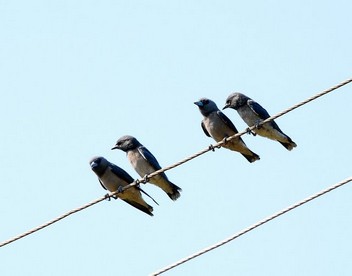

But that wasn't why I was in this sun-scorched village in south India. Abhisheka was looking for someone to help with her survey of waterbirds, and I wasn't about to let such an opportunity pass. And so we visited the tanks and counted birds by the hundreds - egrets, herons, storks, moorhens, jacanas and kingfishers. The birds that were the highlight of my stay though were the Cinnamon Bitterns, Red Collared Doves and the Ashy Woodswallows chattering animatedly in Palmyra trees silhouetted by the sunset.

There were Bark Geckos and the Fan-throated Lizards aplenty, and a walk by the canal showed us a few baby Checkered keelbacks. The heat prevented us from venturing out most of the day, and so I spent a lot of time in the nursery helping Ruthamma with the saplings. It's a joy communicating with someone without words. We spoke sans words about butterflies and trees and slugs and mosquitoes. Then I also accompanied ATREE "green brigade" for the flying fox census.

Ten days went by in a flash washed in sunshine and lemon juice. Ten days of eating breakfast, lunch and dinner off banana leaves with my hands. Ten days of trying not to spoil Jackie Chan's name. Ten days of birds. Ten days of stalking the insects and frogs in the garden with the 105mm. Ten days of stories that would fill volumes!

- En Chiang Lee

A shield tail’s awful stench - shield against predators

Sheild tails or Uropeltids as they are called are one of the few snakes which are rarely seen and easily missed due to their burrowing habitat in leaf litter laden soil of the forest floor. These relatively small snakes have evolved to lead a life in the underworld - eyes almost non-existing; the head narrow, pointed and sharp; the body smooth and glossy and the tail as if it was unassumingly cut off with an axe and this is how it gets its name as shield tail.

I came across three species of these non-venomous snakes and in two of the occasions, they were seen lying on the road soon after a heavy downpour and on third occasion, it was found underneath the rotting leaf litter when we were searching for snails. The snake which was later identified as Wall’s shield tail" was very quick in disappearing into the litter while the other two on the road, did not have the evolutionary advantage of burrowing into a thick layer of asphalt!

The snakes - one yet to be identified and the other known as the "Pied bellied shield tail" which were found on the road were needless to say picked up for photo documentation and give them a second life by releasing them into the forest away from speeding vehicles. On both occasions, I ended up having a nauseating feeling due to the pungent scent in the urine of the snake which is known to be an anti predatory trait developed over the years. The smell, strong like that of garlic and rotting meat in addition to a weird smell which cannot be put in words took a bucket of water and a good lathery soap to ward off. So good was the evolutionary trait in those snakes that it effectively worked on creatures which try to save it from death too!

- Seshadri K.S.

Goddess watches over forest trail!

It came as a surprise to me, when I saw a white stone idol deep inside the forest about 5 to 6 hours walk from the nearest village near Nettirikal. The idol was covered with a piece of cloth and adorned with garlands which had dried up; probably a month old. I was curious as to what this idol was doing miles away from civilization, when one of my field assistants said it was goddess Pachi-amman!

Locally, people worship her for their safety while travelling in remote areas of the forest. Later, near one of the villages, I had an opportunity to interact with an old man who knew this area well. He told me that in the years bygone, Pachi-amman was worshipped by dacoits who were outlawed and hiding from British and local administrators. That left me wondering if the descendants of these dacoits were still continuing the tradition!

- Chetana H.C.

Forest managers, researchers meet

During 10th and 11th April, 2009, a national level workshop was organized by Agasthyamalai Field Station-ATREE, Singampatti and Kalakad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Mundanthurai to deliberate on mapping and quantification of plant bioresources of Western Ghats at Mundanthurai Forest Range Office.

The research project is funded by Dept. of Biotechnology, Govt. of India. Seven teams with about 30 members belonging to different research and academic institutions have taken up the task of mapping and quantifying the bioresources across Western Ghats. The objective of the meeting was to share their research findings with forest managers besides sharing it among the teams.

Mr.Ramkumar, IFS, CCF & FD inaugurated the meeting and released the issue of Agasthya Newsletter. Mr.Venkatesh, Deputy Director and Pillai Vinayagam, FRO, participated in the meeting.

Dr. Gladwin Joseph, Director, ATREE gave an overview of ATREE’s commitment towards biodiversity conservation at the national level. Prof. Ganeshaiah, explained about the expected output for forest managers from the project towards bioresource management in the entire Western Ghats.

- R Ganesan

Centre for Excellence in Conservation Science

Royal Enclave,Srirampura,Jakkur Post

Bangalore-560064

Telephone: 080-23635555 (EPABX)

Fax : 080- 23530070

Any and all opinions expressed in this newsletter are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinion of ATREE.

Editorial Team

Editor: T. Ganesh

Associate editor: Samuel Jacob

Editorial Review: R. Ganesan, M. Soubadra Devy

Design and presentation:(print) Jahnavi Pai

(web) Vivek Ramachandran

One of the grand old Madhucas that was axed

Photo- Abhisheka Rajagopal

A S H O K A T R U S T F O R R E S E A R C H I N E C O L O G Y A N D T H E E N V I R O N M E N T

Ashy woodswallows chatter away at dusk

Photo: En Chiang Lee

Release of the April issue of Agasthya.

Photo: M. Mathivanan

Residential layouts transforming 'buffer zone' landscape

Photo: T Ganesh

Thar on the run

Photo: Vivek Ramachandran

Pied bellied shield tail .

Photo: Seshadri K.S

'Pachi-amman' watches over forest trails

Photo: Chetana H.C.

Prof. Ganeshaiah planting a sapling at new field-station site

Photo: R Ganesan